By Shanita Jones

Blaaat… plat plat! Blaaaat … plat plat! As I cut through every single tiny white circular pill my hands get a little wearier. It’s been a long, long day, and everything seems a little off track. And I’m tired. Like so tired that I think you’d never understand. But these little tiny pills are yet another concoction that “just might maybe” make a difference in his gait. Or maybe not. You see, it’s all just practice, a trial… no treatment, no cure. I’m lost and sometimes so terrified of tomorrows. BUT! I… CAN… NOT… GIVE… UP! Even with this tired body and these tears streaming down my face, I can’t allow him to see me this way because I never want him to lose hope.

“WHOA! What’s wrong with HIM?!” Insert awkward pause expecting me to give a full report on my child’s health and diagnosis, something we would never do to any other child utilizing the park. “CAN HE TALK? D-O-E-S H-E U-N-D-E-R-Stand?” Insert me explaining once again that his disability is physical and not cognitive, that every person with a disability is not the same. Also insert him becoming very frustrated because he has his own voice and doesn’t need anyone else speaking for him. “Only the strongest mothers are blessed with children with SPECIAL NEEDS!” Insert feel good quote about parents of disabled children with well-meaning but disrespectful language. “You couldn’t possibly have the faith you claim to have because your child would be healed!” Insert long drawn out prayer from someone attempting to douse my kid with oil. “I don’t KNOW how you do it!?!?” As if I’ve ever had the choice to “just walk away.” Or why would you think I would if I could. This is my blood… a living breathing part of me… my heartbeat… MY CHILD! “It’s a good thing you’re in that field, that’s why he was given to you!” What about all the other children whose parents are not in the field. Do you realize it still does not make it easy?

To see your child physically deteriorate before your eyes is a painful thing. To hear people who typically mean well believe that the difference of your child is somehow a gift, is confusing. To see adults stare with mouth fully open at my beautiful boy, makes me sick inside. He is funny. He is a gamer. He loves math. He was the one who shed tears knowing that his Mommy would be going back to school for an advanced degree. He is such a charmer, ask any of his prior or current caregivers. He has so many great things about him that others will never know or take the time to know simply because he’s “different.” He is a human being. He is Tyler.

I too am human. I too once used insensitive words and phrases, not meaning to cause harm. It was through studies and talking to friends, students, and persons I’ve served who are disabled that I learned to do better. I reflect back on just a few weeks ago when my daughter told me in shock, anger, and dismay, “Mommy! He said he does not want a cure, that he’s okay with people taking care of him!” I can still feel the discomfort and embarrassment he exuded for “being exposed.” I remember the sadness I felt. The anger I felt. How could you NOT want a cure? There are people out here fighting every day for a cure; but you are being ungrateful to say you don’t want one?

Just as quickly as my insides began to boil over in hurt, his words caused me to sit back and reflect on words from one of my friends, who also has a disability. A conversation had over two decades ago in which she discussed how while growing up everybody wanted her to walk. That her difficulties in walking as an effect of Cerebral Palsy gave the people around her more desire for her to do so. It made me remember how she spoke of those days when it was hard to go to physical therapy or other therapies just to try to walk. Of how hard it was to get from one place to the other, something that we don’t think about and typically take for granted as able-bodied persons. How it could take her 15, 20, or even 30 minutes for what would take you and I only a few short minutes to accomplish. How painful it would sometimes be and how she came to the realization that the ability to walk was not as important to her as those around her imposed on her. All those sessions of discomfort, only to please everyone around her. That is until she one day had the courage to say, “Hey I don’t wanna do this anymore. I’m okay with using my chair.”

I remember the empowered sound of her voice when sharing this information with me. Likewise, I remember how sad my heart was that I too wanted her to walk again and I too wanted to stretch her so that she could “get better.” That I too was guilty. The same person that was supposed to be helping her. The same person that is supposed to be empowering her. The same person that has been given the opportunity of providing a service to her, wanted exactly the opposite thing of what she wanted for herself.

We must question ourselves as parents, caregivers, supports, therapists, teachers, service providers and clinicians, “What am I here for? Why am I doing this? Is it to innately self-serve OR is it to serve the person that I am supposed to be supporting?” Is it our dreams that we are trying to reach? Is it our broken hearts that we are trying to heal, while inadvertently taking away something that is a part of this person? A part of who they are. Do we take the time to ask them? What do you want? What are your desires? Or are we selfishly by human nature becoming part of the source of pain and frustration.

As the human race, we must learn to reflect every single day when we’re walking past that person with a disability, when we’re working alongside our disabled coworker, when assisting a loved one who is disabled, “What is my goal? Is it to serve them or is it to serve myself? Is it to make my life better and less stressful or is it to increase their quality of life? Am I attempting to fix them or make changes in this world to make it accessible for all.” Once we start doing this, life for all will become better.

Blatt… platt platt. Another day. Another pill. Another moment in which I wish that Ataxia Telangiectasia never infiltrated our lives. Blatt… platt platt. Another day that I am humbled to be a mother and also a service provider on a quest to not “fix” persons living with varying disabilities, but as an ally working daily to make life more equitable for all.

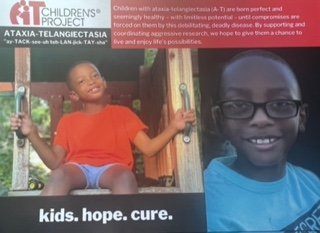

To find out more information on Ataxia Telangiectasia (A-T) a rare condition, please visit the A-T Children’s Project at atcp.org