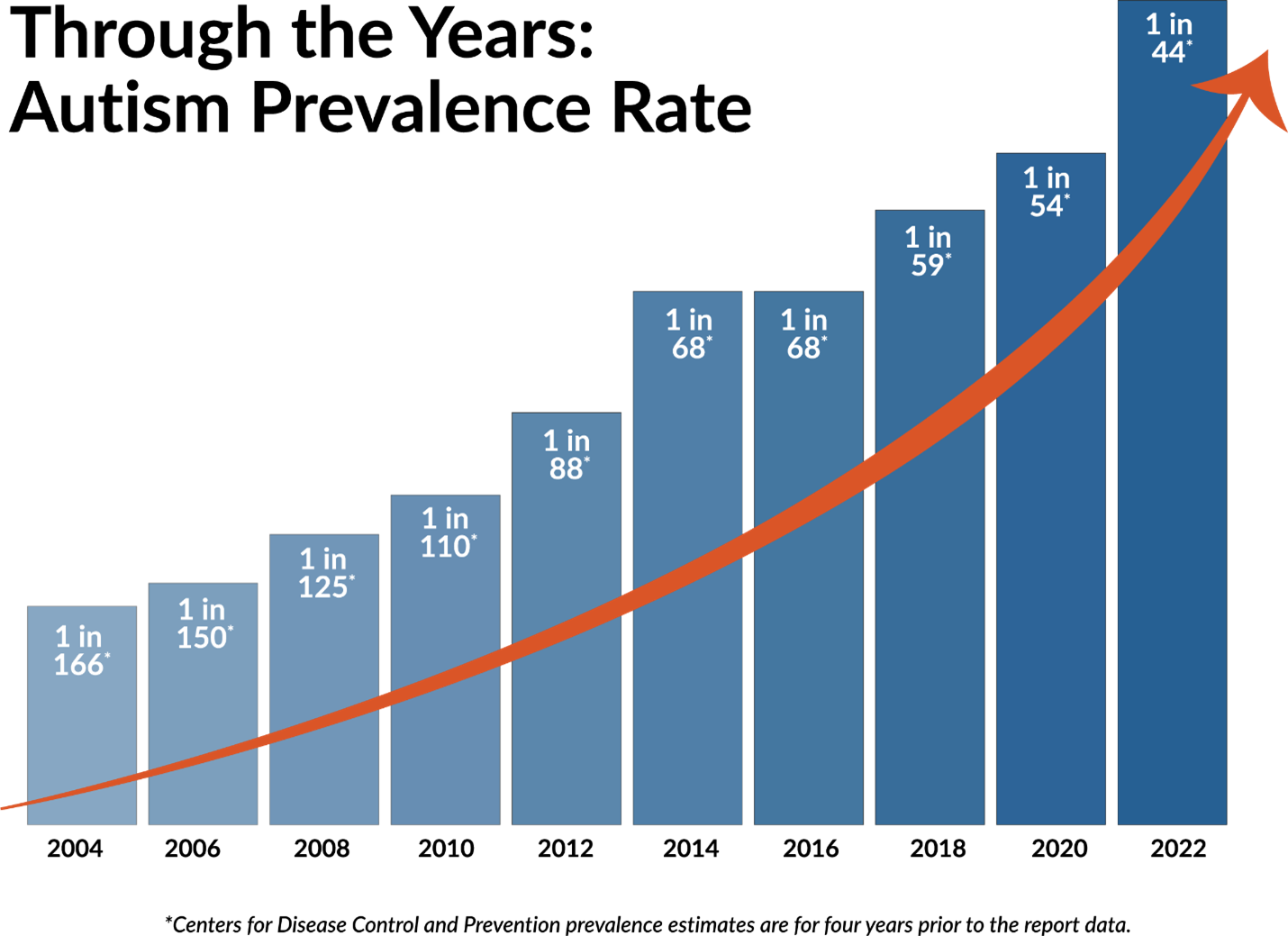

In our rapidly changing world, autism prevalence is also growing. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest report (2018), approximately one out of 44 children is diagnosed with autism in the United States. This is an increase from 2020, in which one out of 54 children was estimated to have autism. About two decades ago, one out of 150 children was estimated to have autism in the United States. So why are autism rates rising? There could be multiple factors contributing to this growing number. One of the factors is the improvements in awareness and response to autism and efforts being made to reach the underrepresented group.

Figure. Graph representing a steady increase in autism prevalence over the past few decades (Southwest Autism Research & Resource Center. https://autismcenter.org/new-autism-prevalence-rate-released-cdc).

However, despite this improvement and effort, there is still evidence of autism diagnosis and treatment disparities, especially experienced by children with autism or with high-likelihood for autism and their families across racial and ethnic minority groups and in low-resource settings. Recently, a few caregivers of young children with high-likelihood for autism, who were both from minority backgrounds and low-resource settings, shared such challenges. They were experiencing an approximately year-long waitlist for the child’s autism diagnosis evaluation and a lack of resources to receive a diagnosis and appropriate services. The common concern expressed by the caregivers was “wasting away” days, months, and potentially a few years without getting the services for the child and missing the time of optimal impact due to delay in diagnosis. These challenges point to the need to address not only the shortage of expert evaluators for early screening, but also identify services that could be provided for children with high-likelihood for autism during their uncertain wait time for the evaluation.

While the surging prevalence reflects an increasing awareness and response to autism, it also demands improved access, decisions and outcome measures of treatment for autism. As a Korean-American and being part of a Korean community, I have had the privilege of working with many Korean families of children with autism. Often, the caregivers have expressed the experience of “cultural clash” with providers (e.g., early intervention providers, ABA therapists) in regards to developmental milestones and childrearing practices, as well as language barriers resulting in a lack of effective communication and building rapport. Even if the child receives a diagnosis early in life, I recognized that these factors could become barriers to receiving effective treatments and thus impact the outcomes for these children.

These experiences combined have contributed to developing a strong understanding of the need to extend the findings of my research studies to improve access to autism diagnosis and meaningful treatment outcome measures that are culturally responsive.

References

Autism Speaks. https://www.autismspeaks.org/science-news/new-study-shows-increase-global-

prevalence-

autism#:~:text=The%20global%20increase%20in%20autism,ability%20to%20measure%20autism%20prevalence.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2018). Prevalence of autism spectrum

disorder among children aged 8 years – autism and developmental disabilities monitoring

network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(6), 1–

23

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Baio, J., Washington, A., Patrick, M., DiRienzo, M., Christensen,

D. L., Wiggins, L. D., Pettygrove, S., Andrews, J. G., Lopez, M., Hudson, A., Baroud, T., Schwenk, Y., White, T., Rosenberg, C. R., Lee, L., Harrington, R. A., Huston, M., et al. (2020). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years — autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries, 69(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1.