CW: Thank you for joining me today as part of a classroom requirement for a lender, I will be interviewing you just asking you some basic questions about yourself and your experiences as an autistic person in higher ed. So, do you mind telling us a little bit about yourself, in general?

Em: So yeah, I, as you said, like, I'm autistic person, I started this graduate program at the start of last school year. So, this is my second year finishing the third semester.

CW: Great. Can you tell us like some of your interests, like research areas of interest?

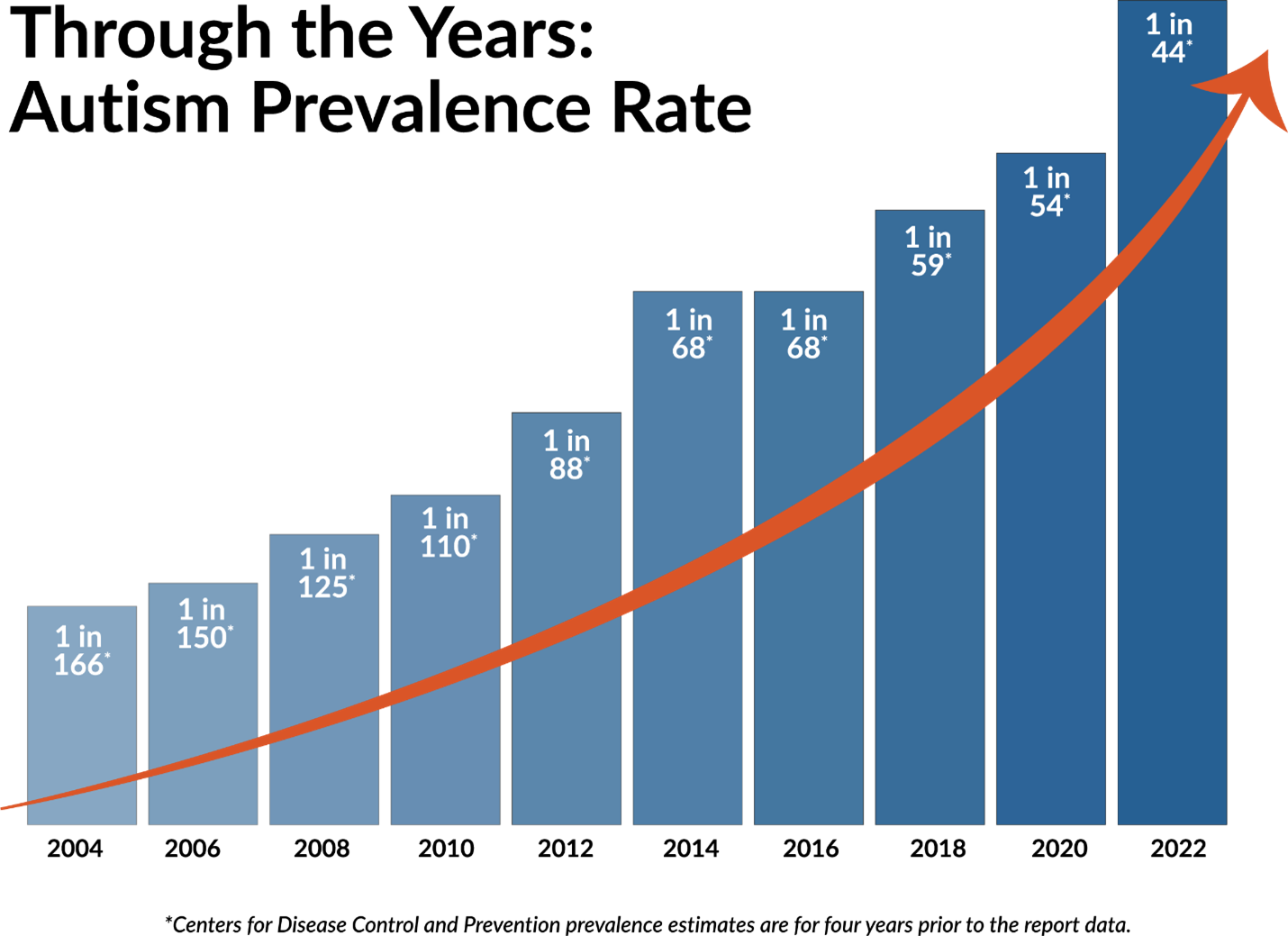

Em: Yeah, so as an autistic person, I am interested in research pertaining to autistic folks, but I, want to do research that I feel like is more beneficial to actual autistic people. And a lot of my research interests overlaps with, like my own identity and experience. I'm working on a master's thesis right now, that looks into how queer and trans autistic folks create their sexual gender and autistic identities.

CW: Yeah, that's interesting. What sparked your interest in that? Is there a research gap for queer and autistic folks?

Em: I have all those identities, I identify as queer and gender queer. When I look into experiences of like, actual autistic people, like online talking about their identities, it makes a lot of sense, but then whenever I look up these topics, more on the academic side of things, it is very medicalized, it tends to be very medicalized. Like trying to figure out why they like there's this trend but ends up kind of more pathologizing instead of celebrating identity development. For instance, kind of almost treating the medicalized idea of gender dysphoria as a co-occurrence with being autistic. Which I feel like can kind of be problematic, like, that's not saying like, autistic people don't experience gender dysphoria, but is the way it is medicalized. But that assumes that only like occurs in this certain way which I find problematic.

CW: I'm curious, as an autistic person, what's your experience been like? Whether good or bad, and maybe you could provide a few examples?

Em: Yeah, I would say overall, it's been good. I wasn't formally diagnosed until high school. And I wasn't really given accommodations until then, either. But accommodations were kind of limited to things like standardized testing. It wasn't really considered like, oh I also get extended time when it comes to just the end of the unit tests that teachers make and assign or with assignments. And so that was often a struggle, and I had to advocate for myself because I did not have good case managers.

And when I got to college, I actually did dual enrollment. This occurred with dual enrollment as well, but it was a given that extended time means that you go to a separate testing location, regardless of whether it is a brief quiz or a test or whatever, so that you have more time, they have the quiet environment. But I still had instances where I struggled some. When I first went to college, I went to a very small liberal arts college and they had a great Disability Resource Center. And in retrospect, I think that was because the school so was so small, if I was ever having any issues with anything, I could just walk in and talk to one of the two directors who worked there, and they were the only employees, they just always had open office hours like that, and would come up with very creative solutions. In fact, I've come back to those ideas since I came into grad school like using PDF to text readers to like to listen to readings to save some time, instead of trying to just sit down and read everything.

Em: So, when it got to the following fall semester, where I was having a lot of my executive functioning just completely slow down due to the pandemic circumstances. And a lot of people don't understand that executive functioning really, in its most basic terms, just means that like, your brain functions differently and sometimes slower. A lot of people equated with time management issues, which is not necessarily the case. For all autistic people, you can have issues with time management and not have issues with executive functioning and vice versa. So I was having to basically advocate for myself that I had extended time accommodations, and to get more time to complete a final and I ended up getting like a lot the patronizing language of ‘oh, you should be lucky that you got this because the real world isn't this way,’ when in fact, the real word is, because I am allowed accommodations. And I felt like the, that spring semester, spring 2020, when the pandemic first started, I also had to get incomplete in a class and I had all these issues, and the DRC wasn't really there to help me.

CW: It sounds like you have had to do a lot of self-advocacy. If you had to give recommendations to other autistic folks who are in higher ed, is there something that you would really want them to know about self-advocating?

Em: That's a good question. Because I think the unfortunate reality is self-advocacy to an extent like is self-taught. It is a survival skill. I think what I will say is that, this doesn't quite answer your question, but if this was to be advice in terms of like, how to survive college, I would say it is very helpful to try to meet with Disability Resource Centers to figure out how they handle accommodations. I remember when I was touring undergrad schools, there was this one private women's college I considered going to, but since it was private, they're like, ‘oh if you have accommodation needs, you just talk to like the dean of your school, and they'll handle it for you.’ That is such a big red flag for me. There wasn't actually a department? So, just try to go to a school that has good Disability Resource Center, and then go ahead and try to make sure you can get all the accommodations that you can, so if you run into a situation where you need to use them, you can say, ‘Hey, I have this.’

CW: What is your experience in our department been like? Has it been what you've hoped for considering that they have large disability presence?

Em: I have accommodations, but it's been hard to figure out I guess, it’s not as straightforward as how to implement those as it is with the way undergrad is set up. And so, it's it has really come down to more the pedagogy that like instructors have. So, for example, the way Dr. Smith and Dr. Miller’s classes were set up were very beneficial. And I found very helpful, because you had that two- or three-day grace period and those in instructors in general, were very understanding if you needed more time, but they also [were] trying to break away as much from the academic institution as possible. So, those classes I felt very comfortable in and they're very big on expressing your access needs and stuff like that.

And then there was course A, which was a mess. We knew we had a final, but we weren't actually told what that final was until the last five minutes of the last class. And that just ended up being a mess for me as it was for everyone. I'm recalling the group chat of where there were people who like pulled 48 hours to get everything done on time.

CW: Yeah, I remember that.

Em: I never stayed up past midnight to complete assignments until that semester. I remember I was like, up until like 1:30 AM. And it was Saturday morning, and I ended up emailing Dr. Smith, I was like ‘Hey, I'm not done with your assignment, because it was now the end of the two day grace period. I'll get this done like later today.’ And Dr. Smith emailed me back, ‘That's what your accommodations are for, when you run into situations like this.’ That was the first time I had someone really acknowledged what those accommodations were really for. So many instructors are like, ‘Oh, you can get extended time, but you need to let me know like way in advance if you need the extended time.’ Not realizing that sometimes you don't know how long things will take you some time, and all these other factors that just come from having a disability.

CW: So, if I hear what you're saying is: if you could change university systems for autistic folks, you’d recommend more flexibility in deadlines, greater attention to the accommodations and more awareness of that people have different disabilities?

Em: Yeah, there is definitely power with more awareness of different disabilities. Because one thing I personally noticed, there seems to be a greater understanding of disability. But for instance, people might have more understanding of physical disabilities, and they don't quite understand what it's like, for invisible disabilities. That's just an observation I'm making. It's not in terms of favoring one disability over the other, it's actually like they're more specialized in one area, that they don't quite realize that it's not a one size fits all.

I would also add that while it is important to have self-advocacy skills, I would personally benefit from having someone to advocate for me on behalf. When I finally shared with my advisor what had happened to me at the end of last Fall semester she was like ‘if anything ends up happening to you like that again please let me know and I will help you advocate for you.” And like, I never had anyone tell me that before, because sometimes it is a lot to be able to self-advocate for yourself, and people don’t listen. It is stressful and to be able to have an ally who is perceived as being “higher up” to be able to do that for you when you need it, it is really helpful. I think we need more allies to help advocate for disabled students when self-advocacy is not enough.

Special thanks to Em for her time and sharing her perspective.